1. Introduction

This report provides a comprehensive, data-driven analysis of the National Health Service (NHS) in England, examining its current operational performance, workforce dynamics, financial landscape, digital transformation efforts, procurement strategies, and patient experience. Drawing on recent data from NHS England, the House of Commons Library, Nuffield Trust, King’s Fund, Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), Care Quality Commission (CQC), and the National Audit Office (NAO), it aims to offer a multi-faceted understanding of the pressures facing the NHS and its strategic responses.

The NHS in England has faced increasing demand and declining performance across key waiting time measures even before 2020. These pressures have significantly intensified following the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to record waiting lists, prolonged emergency care delays, and persistent workforce challenges. The analysis delves into these issues in detail, highlighting both the immediate operational strains and the systemic factors contributing to the current state.

The main source of this analysis is the NHS statistics : England Report published by government and available to view directly here.

2. Operational Performance and Patient Access

2.1 Emergency Care: A&E and Emergency Admissions

Emergency care services in England continue to operate under significant strain, with demand consistently challenging capacity. In the three months ending April 2025, major hospital Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments experienced an average of 46,200 daily attendances. Concurrently, minor A&E facilities, such as walk-in centres and minor injuries units, saw an average of 28,200 daily attendances. Over the preceding twelve months, this amounted to approximately 16.8 million attendances at major A&E and 10.0 million at minor units. These figures represent a notable increase over time; attendances at major departments are 16% higher than ten years ago, while minor departments have seen a 41% increase in daily attendances.1

The onset of COVID-19 lockdowns in April 2020 led to a sharp, temporary reduction in A&E attendances, with Type 1 (major) attendances falling by 48% and Type 3 (minor) attendances by 72% compared to April 2019. However, following this initial dip, attendances at Type 1 departments returned to and have largely remained above pre-pandemic levels since mid-2021. Type 3 attendances took longer to recover but have consistently exceeded pre-pandemic levels since May 2023.1

The standard for A&E waiting times dictates that 95% of patients should spend less than four hours in the department. This target has been consistently missed for several years. In 2013/14, 6.5% of patients attending major A&E departments waited over four hours; this proportion escalated to 41.9% in 2023/24. Performance reached its nadir in December 2022, when over half (50.4%) of major A&E patients endured waits exceeding four hours. As of April 2025, the figure stood at 40%.1

The initial COVID-19 lockdowns, which led to a temporary reduction in A&E attendances, also saw a brief improvement in four-hour wait performance. However, the subsequent period has seen attendances not only return to but surpass pre-pandemic levels, while performance on four-hour waits has significantly deteriorated to record lows. This trajectory suggests that the pandemic did not merely disrupt services; it appears to have exacerbated underlying systemic issues, resulting in a higher baseline demand and a diminished capacity to manage it. This could stem from accumulated health needs, shifts in patient behaviour, or ongoing operational inefficiencies. Consequently, the NHS is not simply recovering to its pre-pandemic state; it appears to be operating under a new, higher-pressure equilibrium where demand more severely outstrips capacity.

Emergency admissions also reflect increasing pressure. In April 2025, there were approximately 396,900 emergency admissions to hospital via all A&E departments, averaging 13,200 people per day. An additional 132,300 emergency admissions, averaging 4,400 per day, occurred through routes other than A&E. Prior to the pandemic, emergency admissions via A&E had increased by 36% between February 2011 and February 2020. Similar to attendances, admissions via A&E sharply declined during national COVID-19 lockdowns, falling by 36% in April 2020 compared to April 2019. However, admissions have generally followed an upward trend in the past two years, consistently exceeding pre-pandemic levels since May 2023.1

Long waits for emergency admission, often referred to as ‘trolley waits,’ have surged dramatically. The number of patients waiting over four hours for emergency admission after a decision to admit has increased by 531% from 28,100 in April 2015 to 176,900 in April 2025, averaging 5,900 per day. The highest figure recorded for this metric was over 7,200 in December 2022. Waits of 12 hours or more from the decision to admit, once rare (averaging below 50 daily from August 2010 to November 2019), reached an average of 1,500 daily in April 2025, peaking at 2,000 in January 2025. Crucially, new data reveals that 12-hour waits from the time of arrival in A&E are substantially higher, averaging 4,600 patients daily (137,200 total) in April 2025.1

The distinction between “12-hour waits from decision to admit” and “12-hour waits from arrival in A&E” is critical. The significantly higher figures for waits from arrival reveal the true extent of patient suffering and system congestion. The official “trolley wait” metric, which measures from the decision to admit, severely underestimates the actual time patients spend waiting in emergency departments. This suggests that the focus on the “decision to admit” metric may not fully capture the patient experience or the operational bottleneck occurring earlier in the patient journey within A&E. Consequently, public and policy discourse on A&E waits may be understating the severity of the problem, potentially leading to insufficient resource allocation or misdirected interventions. The true pressure point lies in the initial stages of emergency department processing and flow.

Table 2.1: Emergency Care Performance in England (Selected Metrics)

| Metric | Pre-pandemic (Feb/Apr 2020) | Peak Pandemic Impact (Dec 2022 / Jan 2023) | Latest Available (Apr 2025) |

| Average Daily Major A&E Attendances | ~40,000 (Feb 2020) 1 | – | 46,200 1 |

| % of Major A&E Patients Waiting 4+ Hours | ~25% (Feb 2020) 1 | 50.4% (Dec 2022) 1 | 40% 1 |

| Average Daily Emergency Admissions via A&E | ~12,000 (Feb 2020) 1 | – | 13,200 1 |

| Avg Daily Patients Waiting 4+ Hours for Admission (from decision to admit) | ~1,000 (Feb 2020) 1 | >7,200 (Dec 2022) 1 | 5,900 1 |

| Avg Daily Patients Waiting 12+ Hours for Admission (from decision to admit) | <50 (Nov 2019) 1 | 2,000 (Jan 2025) 1 | 1,500 1 |

| Avg Daily Patients Waiting 12+ Hours from A&E Arrival | – | – | 4,600 1 |

2.2 Planned Hospital Treatment: Waiting Lists and Targets

The waiting list for hospital treatment in England, known as the “elective care” or “Referral-to-Treatment (RTT)” waiting list, stood at approximately 7.4 million as of March 2025. This figure represents an estimated 6.3 million unique patients, indicating that some individuals are awaiting more than one procedure.1

Historically, the waiting list demonstrated consistent growth long before the pandemic. Between 2012 and 2019, it increased significantly, reaching over 4.5 million by December 2019, a 74% rise from December 2012. This trend underscores that while the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically accelerated the growth in waiting lists, the underlying increase was already a pervasive challenge for several years prior. The waiting list reached its peak at 7.7 million in September 2023, marking a record high in the current data series, which dates back to August 2007. Since this peak, the list has seen a reduction of approximately 4% but remains elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels.1 The observation that the RTT waiting list was already growing significantly and the 18-week target had not been met for years before the pandemic indicates that the NHS was already struggling with demand-capacity imbalances in elective care. The pandemic, therefore, acted as an accelerant rather than the sole cause of the current backlog crisis. This implies that solutions must address not only the pandemic-induced backlog but also the deeper, long-standing structural issues of demand management and capacity constraints that existed prior to 2020. Simply returning to pre-pandemic performance levels would still mean missing established targets.

The NHS Constitution Handbook stipulates that 92% of patients referred for consultant-led treatment should commence treatment within 18 weeks. This target was consistently met from January 2012 to November 2015. However, it has not been achieved since early 2016. By January 2020, just before the pandemic, the 92nd percentile waiting time had risen to 25 weeks. The pandemic further exacerbated this, with waiting times peaking at 52 weeks in February 2021 due to reduced treatment activity. Although waiting times have remained higher than pre-pandemic levels, there has been a general downward trend recently. As of March 2025, the 92nd percentile waiting time was approximately 42 weeks, which is 10 weeks lower than the peak in February 2021 but still significantly above the target.1

There is also a “zero tolerance” policy for patients waiting longer than 52 weeks for treatment. Following the introduction of RTT targets, the number of such waits initially fell sharply. However, a rise to over 3,000 52-week waiters occurred in 2018. The reduction in elective care activity during the pandemic led to a massive surge, with numbers peaking at around 436,000 in March 2021. Since September 2023, the number of one-year waiters has consistently fallen. As of March 2025, approximately 180,000 people were waiting over 52 weeks, representing a 59% decrease from the peak. Despite this progress, NHS England had aimed to eliminate 52-week waits by March 2025.1

While the waiting list has decreased by 4% from its peak and 52-week waits have significantly reduced, the 18-week target remains far from being met. This suggests that the substantial efforts to reduce the longest waits (e.g., those exceeding 52 weeks) might be consuming capacity that would otherwise contribute to reducing the overall list or improving performance against the 18-week target. This implies a strategic prioritization of the most severe cases, potentially at the expense of achieving broader, faster access for the majority of patients. The NHS faces a complex trade-off between tackling the most egregious long waits and improving average waiting times for all patients. Achieving the 18-week target of 65% nationally by March 2026 and reducing 52-week waits to less than 1% of the total waiting list by the same date will require substantial, sustained effort and potentially new models of care delivery.2

Table 2.2: Planned Hospital Treatment Waiting List and Performance

| Metric | Dec 2012 | Dec 2019 | Feb/Mar 2021 (Peak) | Sep 2023 (Peak) | Mar 2025 |

| RTT Waiting List (million) | ~2.6 1 | >4.5 1 | – | 7.7 1 | 7.4 1 |

| Estimated Unique Patients on RTT List (million) | – | – | – | – | 6.3 1 |

| 92nd Percentile Waiting Time (weeks) | <18 1 | 25 1 | 52 1 | – | 42 1 |

| Number of Patients Waiting Over 52 Weeks | – | ~4,500 1 | 436,000 1 | – | 180,000 1 |

2.3 Cancer Services: Diagnosis and Treatment Standards

Cancer waiting times in England are subject to specific standards and have experienced significant fluctuations. The backlog of patients waiting over 62 days for cancer treatment after an urgent GP referral with suspected cancer was approximately 11,000 in early March 2020. This figure surged to 34,000 by late May 2020, before gradually falling back to around 16,000 by December 2020. The backlog increased again in late 2021 and mid-2022, peaking at 33,950 in September 2022. As of late March 2025, the backlog had reduced to 14,512, a figure similar to that for late March 2024.1

The 28-day Faster Diagnosis Standard, which requires 75% of patients to be diagnosed or have cancer definitively ruled out within 28 days of urgent referral, has been in place since September 2021. This standard was met for the first time in February 2024, with performance at 78.1%. In March 2025, performance further improved to 78.9%.1

The 31-day Treatment Standard dictates that 96% of patients should be treated within 31 days of a decision to treat. This new standard, which now covers approximately twice as much patient activity by including subsequent treatments, has shown performance levels similar to the old target. The previous target was consistently met until 2019 but has been breached every month since January 2021. Performance reached a record low of 87.5% in January 2024, but subsequently improved to 91.4% in March 2025.1

The 62-day Treatment Standard, requiring 85% of patients to be treated within 62 days of referral, has undergone a significant change. Previously, it measured waits only after GP referral; now, other referral routes are included, covering around 43% more patients. While the 85% target remains unchanged, this broader inclusion effectively eases the performance target slightly, as it improves reported performance by several percentage points compared with the old standard. The previous target was not met after 2015, with performance remaining below 80% since 2018. A record low of 54.7% (under the old measure) was observed in January 2023. In March 2025, under the new measure, 71.4% of patients were treated within 62 days of referral.1

The change in the 62-day cancer treatment standard to include more referral routes, while maintaining the 85% target, has been noted to “effectively ease” the target by statistically improving reported performance. This suggests that some reported improvements might be a consequence of methodological changes rather than purely operational gains. While broader inclusion of referral routes is beneficial for a comprehensive view, it complicates direct historical comparison and could obscure the true operational improvement still required to meet the underlying demand. Policymakers must therefore exercise caution when interpreting “improved” performance figures, discerning whether they reflect genuine operational advancements or shifts in measurement methodology. The underlying capacity and resourcing issues may persist despite better-looking statistics.

Despite some improvements from their lowest points, the 62-day (71.4% vs. 85% target) and 31-day (91.4% vs. 96% target) treatment standards are still significantly missed. The 28-day Faster Diagnosis standard is the only one consistently met recently. This pattern suggests that the primary bottleneck in cancer care is not in initial diagnosis, but rather in the subsequent stages of the treatment pathway. This could be attributed to limitations in diagnostic capacity, theatre availability, or shortages of specialist workforce. Consequently, efforts need to be concentrated on streamlining the post-diagnosis treatment initiation phase, which currently appears to be the weakest link in the cancer care pathway, in order to meet the ambitious 2025/26 targets of 75% for the 62-day standard and 80% for the 28-day Faster Diagnosis Standard.2

Table 2.3: Cancer Waiting Time Standards Performance

| Standard | Pre-pandemic (Jan 2020) | Peak Pandemic Impact (Jan 2023) | Latest Available (Mar 2025) | Target |

| 28-day Faster Diagnosis Standard (%) | – | – | 78.9% 1 | 75% 1 |

| 31-day Treatment Standard (%) | >96% (met) 1 | 87.5% (Jan 2024) 1 | 91.4% 1 | 96% 1 |

| 62-day Treatment Standard (%) (old measure) | <80% 1 | 54.7% 1 | – | 85% 1 |

| 62-day Treatment Standard (%) (new measure) | – | – | 71.4% 1 | 85% 1 |

2.4 Ambulance Services: Response Times and Demand

Ambulance services in England categorize calls into four levels of severity, each with distinct response time standards. Category 1 calls, for immediate life-threatening conditions, aim for an average response under 7 minutes and 90% within 15 minutes. Category 2 calls, for serious conditions, target an average response under 18 minutes and 90% within 40 minutes. Category 3 (urgent problems) and Category 4 (non-urgent problems) aim for 90% arrival within 2 hours and 3 hours, respectively. These standards have been consistent since 2018.1

Actual response times have faced considerable challenges. Record waiting times were observed in winter 2022/23. In December 2022, the average response time for a Category 1 call peaked at 10 minutes 57 seconds, significantly exceeding the 7-minute target. For Category 2 calls, the average response time reached nearly 1 hour 32 minutes in December 2022, far surpassing the 18-minute target. While performance improved in winter 2023/24, the mean average response time targets for Category 1 and 2 calls are still not being met as of April 2025. The 90th percentile target for Category 1 calls has been met in recent months, but those for Category 2, 3, and 4 calls remain unmet.1

Demand trends indicate a notable increase in the severity of calls. The number of Category 1 ambulance incidents, representing the most serious cases, has risen in recent years. In April 2025, there were, on average, 2,518 Category 1 ambulance incidents every day, marking a 33% increase from April 2019, when the daily average was 1,894 incidents. In contrast, the number of Category 2 ambulance incidents per day in April 2025 was similar to pre-pandemic levels.1

The significant increase (33%) in Category 1 calls, while Category 2 demand remains stable, indicates a shift towards more critically ill patients requiring immediate, life-saving intervention. This pattern suggests that the pressures on ambulance services are not merely about overall call volume, but fundamentally about the increasing severity of cases. More severe cases inherently demand faster responses and more intensive resources. This trend places immense strain on the most critical end of the emergency care pathway, potentially leading to increased mortality or poorer outcomes for the most vulnerable patients, even if overall call volumes do not dramatically surge. It also suggests that upstream issues, such as difficulties in accessing GP appointments or delays in hospital discharges, might be contributing to patients becoming sicker before they necessitate an ambulance.

While ambulance response times are directly measured, their ability to meet targets is heavily influenced by hospital handover delays, where ambulances are unable to offload patients at A&E departments. The fact that Category 1 and 2 targets continue to be missed, despite some improvements, points to persistent issues in patient flow within hospitals, which prevent ambulances from returning to service quickly. This directly links to the A&E waiting times and delayed discharge issues discussed previously. Therefore, improving ambulance response times requires a whole-system approach that extends beyond simply investing in more ambulances or paramedics. It necessitates addressing A&E overcrowding and ensuring timely patient discharge to free up hospital beds, thereby enabling faster ambulance turnaround. The 2025/26 target to improve Category 2 response times to an average of 30 minutes is ambitious given these systemic challenges.2

Table 2.4: Ambulance Response Times and Demand (Category 1 & 2)

| Metric | April 2019 (Pre-pandemic Demand) | Dec 2022 (Peak Response Times) | April 2025 (Latest) | Target |

| Category 1 Mean Response Time (min:sec) | – | 10m 57s 1 | – | <7m 1 |

| Category 1 90th Percentile Response Time (min:sec) | – | – | – | <15m 1 |

| Category 2 Mean Response Time (min:sec) | – | 1h 32m 1 | – | <18m 1 |

| Category 2 90th Percentile Response Time (min:sec) | – | – | – | <40m 1 |

| Average Daily Category 1 Incidents | 1,894 1 | – | 2,518 1 | – |

| Average Daily Category 2 Incidents | – | – | Similar to pre-pandemic 1 | – |

2.5 Diagnostic Tests: Volume, Waiting Times, and Waiting Lists

The volume of diagnostic tests commissioned by the NHS in England has seen substantial growth. In 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 23.6 million diagnostic tests were performed, representing a 48% increase from 2010. Specific test types experienced even more significant growth: MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) tests rose by 84%, CT (computed tomography) tests by 92%, and non-obstetric ultrasounds by 48%. During the first national lockdown in April 2020, diagnostic activity sharply declined by 68% as hospitals redirected resources to focus on COVID-19. However, diagnostic activity recovered and surpassed pre-pandemic levels in 2023, with a 10.7% increase in March 2025 compared to March 2024. The overall trend indicates that the daily average number of tests has almost doubled since 2010.1

Despite this increased activity, waiting times for diagnostic tests remain a significant challenge. The NHS target is for less than 1% of people to wait more than 6 weeks for a diagnostic test. This target was met consistently from February 2009 to November 2013. However, performance deteriorated thereafter, with 4.4% of patients waiting over 6 weeks in January 2020. During the pandemic, waits surged dramatically, peaking at 58.5% in May 2020. As of March 2025, 18.4% of patients were still waiting longer than 6 weeks, significantly missing the NHS recovery plan’s ambitious aim of reducing this proportion to 5% by March 2025.1

The number of diagnostic tests performed has almost doubled since 2010 and increased by over 10% in the last year, indicating significant activity and improved productivity in terms of output. However, waiting times and waiting lists remain stubbornly high, far exceeding targets. This situation suggests that while the NHS is conducting more tests, the demand for tests is growing even faster, or the existing backlog is so immense that increased activity alone is insufficient to clear it quickly. This implies that simply increasing the volume of tests may not be enough to resolve the diagnostic backlog and improve waiting times. A more fundamental re-evaluation of demand management, referral pathways, and potentially the integration of new technologies, such as Community Diagnostic Centres, is required to close the persistent gap between capacity and escalating need.

The waiting list for diagnostic tests also remains substantial. As of March 2025, 1.70 million people were on the waiting list, a considerable increase from 1.01 million in December 2019, just before the pandemic. Following a brief dip in the waiting list during the early stages of the pandemic, there was an unusual and consistent rise from 2021 onwards, with the list remaining at high levels.1 The failure to meet the 5% target for patients waiting over 6 weeks for a diagnostic test by March 2025 (actual 18.4%) indicates a significant challenge in the recovery plan. This suggests that the initial projections for recovery were overly optimistic or that the underlying issues, such as workforce shortages, equipment availability, or patient flow bottlenecks, were more entrenched than anticipated. This missed target for diagnostics has ripple effects across the entire system, as delayed diagnoses can lead to later, more complex, and ultimately more costly treatments, thereby exacerbating waiting lists in other areas like elective care and cancer services.

Table 2.5: Diagnostic Test Performance in England

| Metric | 2010 | 2019 | May 2020 (Peak Wait Time) | Mar 2025 | Target (6-week waits) |

| Annual Diagnostic Tests (million) | ~16 1 | 23.6 1 | – | – | – |

| % of Patients Waiting 6+ Weeks for Diagnostic Test | – | 4.4% (Jan 2020) 1 | 58.5% 1 | 18.4% 1 | <1% 1 |

| Diagnostic Test Waiting List (million) | – | 1.01 (Dec 2019) 1 | – | 1.70 1 | – |

2.6 GP Appointments: Access and Modality

Primary care, particularly GP services, represents a critical access point for patients, and its performance significantly influences the wider NHS. In April 2025, an estimated 29.3 million appointments occurred at GP surgeries in England, which is approximately 13% more per working day than in April 2019, prior to the pandemic. Activity saw a substantial drop of 32% in April 2020 during the initial COVID-19 lockdowns but has consistently risen above pre-pandemic levels since mid-2021.1

The modality of GP appointments has shifted considerably. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, around 84% of appointments were conducted face-to-face. This proportion significantly dropped to approximately 50% during the early stages of the pandemic. While it rose back to 60% before the January 2021 national lockdown, it subsequently fell again. The proportion of face-to-face appointments steadily increased between 2021 and 2023. However, in recent months, this trend has reversed, with face-to-face appointments standing at 65.3% in April 2025.1

Patient access to GPs faces severe challenges. Between March 2020 and March 2024, the number of patients registered with a GP in England increased by 5%, from 60 million to 63 million. Looking further back to March 2016, the increase was 10%. However, over the same 8-year period since 2016, the number of fully qualified GPs per 100,000 patients has decreased by 15%, from 51 to 44 full-time equivalents. This imbalance places unsustainable pressure on the primary care workforce.3 This combination of increasing patient registrations, decreasing fully qualified GPs per patient, and declining patient satisfaction with access (especially phone contact and long waits) creates a direct pathway for patients to bypass primary care. This “GP access cascade” funnels non-emergency but urgent cases into emergency departments and NHS 111, exacerbating pressures on these already strained services. Strengthening primary care access is therefore not just about improving patient experience; it is a critical lever for alleviating pressure across the entire NHS system, particularly in emergency care. The 2025/26 priority to improve patient experience of GP access is foundational to broader system stability.2

Excessive workloads are a major concern, with a July 2024 poll indicating that over three-quarters of GPs (76%) believe patient safety is being compromised by their workload. This is partly due to pressures from hospitals, such as unsuccessful referrals, which mean patients require longer GP care while awaiting hospital treatment. Long waiting times for appointments are prevalent: the number of people waiting more than two weeks for a GP practice appointment increased by 18% from 4.2 million in February 2020 to 5 million in March 2024. Those waiting over 28 days also increased from approximately 1 million to 1.4 million over the same period. Regional variations in access are significant, with rural areas, particularly the South West, experiencing higher proportions of long waits.3

Patient satisfaction with GP access is declining, with 34% of respondents in March 2024 feeling their wait for their last appointment was too long. Difficulties contacting practices by phone are common, often involving long queues and leading some patients to give up or feel like a “burden.” The impact on emergency care is profound: difficulties in securing timely GP appointments often lead patients to seek care from NHS 111 (47% of those with difficulty accessing GP care) or A&E (24%), thus increasing pressure on these acute services.3

While online booking systems can improve efficiency for some, the CQC report highlights that digital exclusion, particularly due to language barriers or lack of technology access, creates inequitable access. Patients with limited English struggle with digital apps and distrust translation software, effectively being excluded from a potentially faster access route. This indicates that digital transformation in primary care must be carefully managed to ensure it does not worsen health inequalities. A multi-channel approach that caters to diverse patient needs, including robust non-digital access points and culturally competent support, is essential for equitable access.

Table 2.6: GP Appointments and Access in England

| Metric | Feb/Apr 2020 (Pre-pandemic/Peak Pandemic Impact) | Mar/Apr 2024/2025 (Latest) |

| Total Monthly GP Appointments (million) | 22 (Feb 2020) 3 | 29.3 (Apr 2025) 1 |

| % of Face-to-Face Appointments | 84% (Pre-COVID) / ~50% (Apr 2020) 1 | 65.3% (Apr 2025) 1 |

| % of Patients Waiting >2 Weeks for GP Appointment | – | 17% (Mar 2024) 3 |

| Patients Waiting >2 Weeks for GP Appointment (million) | 4.2 (Feb 2020) 3 | 5.0 (Mar 2024) 3 |

| Patients Waiting >28 Days for GP Appointment (million) | 1.0 (Feb 2020) 3 | 1.4 (Mar 2024) 3 |

| Fully Qualified GPs per 100,000 Patients | 51 (Mar 2016) 3 | 44 (Mar 2024) 3 |

2.7 Bed Availability and Discharges: Capacity and Flow

Bed availability and occupancy are critical indicators of hospital capacity and patient flow. In the quarter ending March 2025, the NHS in England had an average of 132,178 total beds available, of which 106,068 were general and acute beds, constituting approximately 80% of all hospital beds. While the total number of beds has fallen by about 3% over the last ten years, the number of general and acute beds in March 2025 is similar to the figure from March 2015. General and acute bed availability decreased by 9% between 2011 and 2019, with a further reduction at the beginning of the pandemic due to measures implemented to limit the spread of COVID-19. By the end of 2023, bed numbers, including general and acute beds (104,455 in December 2023 vs. 101,598 in December 2019), returned to pre-pandemic levels. Occupancy rates also returned to pre-pandemic levels, standing at 91.6% in December 2023 compared to 92.0% in December 2019. The long-term trend, dating back to 1987, shows a general decline in bed availability, influenced by increased use of day surgery and a shift towards community-based care.1

A significant challenge to hospital flow is the number of patients who no longer meet the criteria to reside in hospital but remain in beds due to discharge delays. Since 2022, NHS England has published daily information on these patients. In April 2025, an average of 12,740 patients remained in hospital daily who did not meet the criteria for acute care, representing roughly one in ten general and acute beds.1 Despite bed availability returning to pre-pandemic levels and occupancy remaining high, the significant number of patients who no longer meet criteria to reside in hospital highlights a critical flow problem. This is not necessarily a lack of beds, but an inability to discharge patients efficiently, which effectively reduces the functional capacity of the system. This issue directly links to A&E overcrowding and ambulance handover delays. Therefore, simply increasing bed numbers without addressing discharge bottlenecks will not solve the capacity crisis. Investment and policy focus must shift to improving patient flow out of hospitals, which heavily depends on the availability and integration of community and social care services.

For patients with stays of at least 14 days, an average of 9,309 people were delayed each day in March 2025. The causes of delay are categorized into five areas: hospital process (1,754 delays), wellbeing concerns (514), care transfer hub process (1,200), interface process (2,639), and capacity (3,203). “Capacity” is the most common reason for delayed discharge, but it encompasses delays due to both NHS and social care issues. The single largest reason within the “capacity” category (966 delays) is the lack of ‘bed-based rehabilitation, reablement or recovery services,’ which are often jointly commissioned by health and social care. Only 12% of total delayed patients (1,082 out of 9,309) are solely attributable to social care (e.g., lack of home-based social care, residential/nursing care, or waiting for existing social care to restart).4

The publicly available data on delayed discharges from NHS hospitals indicates that it is difficult to definitively state the exact proportion caused solely by a lack of adult social care capacity. While only 12% of delayed discharges are directly attributable to social care according to the new data, the largest “capacity” delays are due to a lack of ‘bed-based rehabilitation, reablement or recovery services’, which are often jointly commissioned or rely heavily on social care elements. The decision by NHS England to stop separating health and social care reasons for delay in 2020, while aiming to foster system responsibility, has inadvertently obscured the precise contribution of social care deficiencies. This situation can create a “blame game” where social care is often disproportionately blamed, despite the inherent complexity of the delays. A more granular and transparent breakdown of delayed discharge reasons, distinguishing between health and social care components, is crucial for targeted policy interventions and equitable resource allocation. The current data structure may hinder effective problem-solving and perpetuate misperceptions about where the primary bottlenecks lie.4 It is important to note that between 2010 and 2020, NHS England collected data on “delayed transfers of care,” but this collection has been discontinued. The new data on discharge delays, published since 2022, cannot be directly compared with the old data.1

Table 2.7: Bed Availability and Discharge Delays in England

| Metric | Dec 2019 (Pre-pandemic) | Dec 2023 | Mar 2025 | Apr 2025 |

| Average Total Beds Available | – | – | 132,178 1 | – |

| Average General & Acute Beds Available | 101,598 1 | 104,455 1 | 106,068 1 | – |

| General & Acute Bed Occupancy Rate (%) | 92.0% 1 | 91.6% 1 | – | – |

| Average Daily Patients Not Meeting Criteria to Reside (Discharge Delays) | – | – | – | 12,740 1 |

| % of Delayed Discharges Solely Attributable to Social Care (of total delays) | – | – | 12% (Mar 2025) 4 | – |

2.8 Discontinued Data Collections

Some data collections previously included in NHS statistical publications were suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic and have not resumed. These include delayed transfers of care (replaced by new, non-comparable discharge delay metrics), cancelled urgent operations, and critical care capacity. Other datasets, such as cancelled elective operations and mixed-sex accommodation breaches, have resumed but are not currently included in the main publication.1 The discontinuation and replacement of certain data collections, particularly delayed transfers of care, mean that direct, long-term comparisons of these critical performance indicators are no longer possible. While new data provides current insights, the inability to track trends over time limits a full understanding of the long-term impact of policies and interventions. This data discontinuity can hinder robust historical analysis and accountability, making it challenging to assess the true effectiveness of pre- and post-pandemic strategies in these specific areas.

3. Workforce Dynamics and Strategic Planning

3.1 Staffing Levels: GPs, Hospital Doctors, and Nurses

Workforce levels across the NHS are a critical determinant of service capacity and quality. The number of fully qualified General Practitioners (GPs) in England experienced a 6% decline from 29,320 in December 2016 to 28,249 in April 2025. However, this figure has shown a slow increase since mid-2023, marking the first rise in several years. In contrast, the number of GPs in training has increased significantly, from 5,625 in December 2016 to 9,769 in April 2025. When combining all categories, including trainees, locums, and retainers, the total Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) GPs rose from 34,946 in December 2016 to 38,018 in April 2025.1

Hospital doctors have seen substantial growth. As of February 2024, there were 147,574 doctors in England’s hospital and community health services, representing a 26% increase over five years and a 43% increase over ten years. This growth has been notably steeper since 2020. Analysis by specialty from February 2010 to February 2025 reveals significant variations: Emergency Medicine experienced the largest percentage increase (+129%), followed by Clinical Oncology (+82%) and Radiology (+80%). Psychiatry saw the smallest rise (+28%). The number of Public Health and Community staff decreased by 67%, partly reflecting the transfer of public health services to local authorities in 2013.1

The nursing workforce has also expanded. In February 2025, there were 363,448 nurses in England’s hospital and community health services, a 25% increase over five years. After an initial decline between 2010 and 2013, numbers recovered by 2015, with a large increase observed since 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. By area of work (February 2010 to February 2025), Adult and General Nurses, the largest category, saw the most significant increase (+46%), followed by Children and Young People (+45%) and Maternity and Neonatal (+63%). Mental Health Nurses initially declined but have since returned to and exceeded 2010 levels. Conversely, Learning Disability Nurses and School Nurses have seen a decrease.1

Overall, the number of doctors has increased faster than other NHS staff groups, rising by 54% from 2010 to 2025. Scientific, Therapeutic, and Technical staff are close behind with a 48% increase. Nurses, Midwives, and Health Visitors increased by 31%. Infrastructure support staff, including managers and central functions, initially decreased but are now above 2010 levels. In total, there are 36% more hospital staff than in 2010.1

Despite significant increases in overall NHS staff numbers (36% since 2010) and specific professional groups like doctors and nurses, the system continues to report high vacancy rates, widespread burnout, and declining patient satisfaction related to staffing levels. This situation suggests that the growth in workforce numbers is either not keeping pace with the escalating demand for services, or there are inefficiencies in how the workforce is deployed and utilized, leading to persistent workload pressures. Therefore, simply increasing headcount may not be sufficient to resolve the NHS’s staffing challenges. Strategies must also focus on improving staff productivity, potentially through digital tools and streamlined processes, addressing factors that contribute to burnout, and ensuring that staff are deployed flexibly and effectively to match areas of greatest demand.

The growth in staff numbers has been disparate across specialties and areas of work. While some specialties like Emergency Medicine have seen large percentage increases in doctors, others like Psychiatry have experienced much smaller rises. Similarly, some nursing areas are growing while others, such as learning disability and school nursing, are declining. This uneven growth could create new imbalances and exacerbate existing shortages in less “visible” but critical areas, potentially impacting preventative care and community services. This indicates that workforce planning needs to be highly granular and responsive to specific specialty needs, not just overall numbers, to ensure a balanced and effective healthcare system that can deliver on strategic shifts towards community-based and preventative care.

Table 3.1: NHS Workforce Levels in England (FTE)

| Staff Group | Dec 2016 / Feb 2018 (Earliest Comparable) | Feb 2025 / Apr 2025 (Latest) | % Change (from earliest comparable) |

| Fully Qualified GPs | 29,320 (Dec 2016) 1 | 28,249 (Apr 2025) 1 | -6% |

| GPs in Training | 5,625 (Dec 2016) 1 | 9,769 (Apr 2025) 1 | +74% |

| Total FTE GPs | 34,946 (Dec 2016) 1 | 38,018 (Apr 2025) 1 | +9% |

| Total Hospital Doctors | 109,648 (Feb 2018) 1 | 147,574 (Feb 2025) 1 | +35% |

| Total Nurses | 277,514 (Feb 2018) 1 | 363,448 (Feb 2025) 1 | +31% |

| Total Hospital & Community Health Staff | 1,064,589 (Feb 2018) 1 | 1,376,849 (Feb 2025) 1 | +29% |

3.2 Vacancies and Retention

Despite increases in overall workforce numbers, the NHS continues to face significant challenges with vacancies and staff retention. In March 2025, the total number of NHS vacancies stood at 100,114, representing a vacancy rate of 6.7%. This marks a slight decrease from March 2024, when there were 100,658 vacancies and a rate of 6.9%.1

Breaking down by staff group, the nursing staff vacancy rate was 6.0% (25,632 vacancies) in March 2025, down from 7.5% a year earlier. For medical staff, the vacancy rate was 4.8% (7,679 vacancies), a decrease from 5.7% a year earlier. It is important to note that these figures do not account for instances where vacant roles are being filled by temporary staff, such as agency or bank workers.1 The fact that vacancy figures do not indicate where roles are filled by temporary staff means that reliance on temporary staff can be more costly and may mask the true extent of staffing shortages or retention issues within the permanent workforce. While NHS England aims to reduce agency spending by increasing substantive staff, high reliance on temporary staff can impact continuity of care and team cohesion. Therefore, the reported decrease in vacancy rates might not fully reflect the stability of the permanent workforce or the quality of care provided.

Several factors significantly affect workforce retention. Key issues include work-related sickness and burnout, bullying, harassment, discrimination, and concerns over pay. Basic pay for Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) doctors and nurses fell in real terms (adjusted for inflation) in the year ending September 2023. The government’s 2022/23 pay offer was widely rejected by healthcare worker unions, leading to industrial action throughout 2023 and into 2024.5 The real-terms decrease in basic pay for doctors and nurses, coupled with issues like burnout and poor working conditions, directly impacts staff morale and retention. Industrial action serves as a clear manifestation of this widespread dissatisfaction. If staff feel undervalued or overworked, they are more likely to leave, perpetuating the vacancy cycle. Addressing pay and improving working conditions is therefore not merely a cost consideration but a critical investment in workforce stability and the long-term sustainability of the NHS. The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan’s retention targets will be challenging to achieve without significant improvements in these fundamental areas.

Table 3.2: NHS Staff Vacancy Rates in England

| Metric | March 2024 | March 2025 |

| Total Vacancies | 100,658 1 | 100,114 1 |

| Total Vacancy Rate (%) | 6.9% 1 | 6.7% 1 |

| Nursing Vacancies | – | 25,632 1 |

| Nursing Vacancy Rate (%) | 7.5% 1 | 6.0% 1 |

| Medical Vacancies | – | 7,679 1 |

| Medical Vacancy Rate (%) | 5.7% 1 | 4.8% 1 |

3.3 NHS Long Term Workforce Plan: Objectives and Challenges

The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, published in June 2023, sets out an ambitious strategy to address the enduring staffing challenges. Its key objectives include increasing the overall workforce from 1.4 million FTE in 2021-22 to between 2.3 million and 2.4 million FTE by 2036-37, representing a 65% to 72% increase. Specific targets include doubling medical school places to 15,000 per year by 2031/32, increasing nursing training places by 80% by 2031/32, and adding significant numbers of professionals: 60,000 to 74,000 doctors, 170,000 to 190,000 nurses, 71,000 to 76,000 allied health professionals, and 210,000 to 240,000 support workers.5

The plan also focuses heavily on retention, aiming to reduce the leaver rate from 9.1% in 2022 to a range of between 7.4% and 8.2%. Additionally, it seeks to reduce the proportion of nursing students who leave training from 16% in 2019 to 14% by 2024.5 A key financial objective is to lower agency spending by increasing capacity and making greater use of bank staff to fill vacancies. Cash spending on agency staff is forecast at £2.1 billion for 2024/25, which would represent a significant 38% reduction from 2022/23.5

While the plan has been broadly welcomed by stakeholders, questions have been raised regarding the feasibility of its ambitious training commitments and “stretching” productivity targets (aiming for a 1.5-2% increase). The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has warned that the implications of the planned workforce expansion for the NHS pay bill will necessitate “difficult fiscal decisions at future Spending Reviews.” Furthermore, the plan explicitly states a continued reliance on international recruitment remaining “at least around current levels” until 2030, with a material decrease only foreseen from that point.5

The plan’s reliance on “stretching” productivity targets alongside ambitious training expansion implies that simply increasing staff numbers will not be enough to meet future workforce needs. If these productivity gains are not fully realized, the plan’s projections for meeting demand may fall short, leading to continued pressures on the system. This highlights the interdependency with digital transformation initiatives, as achieving the plan’s objectives requires not only successful recruitment and retention but also fundamental changes in working practices, technology adoption, and organizational efficiency.

The plan explicitly states a continued reliance on international recruitment “at least around current levels” until 2030. However, recent policy changes impacting the social care sector, such as visa restrictions and increased salary thresholds, demonstrate the vulnerability of this recruitment pipeline to external policy shifts.8 If similar restrictions are applied or global competition for healthcare professionals intensifies, the NHS’s ability to meet its workforce targets could be severely compromised. This means that the long-term workforce plan, while aiming for domestic self-sufficiency, has a significant short-to-medium term dependency that is subject to external political and economic factors, posing a substantial risk to its successful implementation.

4. Financial Landscape and Cost Pressures

4.1 Funding Overview: Budget Allocations and Growth Rates

The financial health of the NHS is a constant focus for policymakers. The Labour government, which took office in July 2024, has set healthcare spending in England to grow at 2.9% per year for the 2024/25 and 2025/26 financial years. This growth rate is marginally faster than the 2.4% average observed between 2011/12 and 2023/24, but it still falls below the historic long-run average of 3.7% per year recorded between 1979/80 and 2019/20.9

A cash injection of £22.6 billion was allocated to the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) over the two years leading up to 2025/26 at the autumn budget.9 Additionally, NHS England and DHSC have allocated a substantial annual budget of approximately £6 billion specifically for education and training in 2024/25.10

While a £22.6 billion cash injection appears substantial, a significant portion of this funding is earmarked for specific cost coverage, such as £1.5 billion for increases in employer National Insurance.9 Furthermore, an estimated £16 billion of this additional funding is expected to be absorbed by inflation alone between 2023/24 and 2025/26.9 This means that the real-terms growth in NHS spending for 2024/25 is projected to be less than 2%, and the average real-terms growth over the two financial years 2024/25 and 2025/26 shrinks to 2.6%.9 This growth rate is still below the long-term average. The Nuffield Trust has critically questioned whether this funding represents a genuine “down payment” on future investment or merely a means of “making ends meet” given the escalating costs.9 This implies that the additional funding, while necessary to cover existing cost pressures, is largely reactive and does not enable significant expansion or transformative investment. The NHS is effectively running to stand still, with limited capacity for the “dramatic recovery” promised by political parties.11

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) highlights that health spending accounts for a substantial 39% of day-to-day departmental spending, making it a key governmental priority. The IFS warns that if health funding continues to increase at or near historical average rates, it will inevitably necessitate “real-terms cuts on other ‘unprotected’ departments”.12 This creates a zero-sum game within public finances. This implies that the financial sustainability of the NHS is deeply intertwined with broader government spending priorities. Continued prioritization of the NHS, without a corresponding increase in the overall public spending envelope, will inevitably lead to cuts in other vital public services, creating difficult trade-offs across the public sector.

4.2 Financial Performance: System-Level Deficits and Provider Positions

The financial position of the NHS at the system level continues to be challenging. Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), which comprise Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) and their constituent providers, overspent by £621 million in 2022/23. This aggregated year-end deficit more than doubled to £1.4 billion in 2023/24. This occurred despite the government providing £4.5 billion of additional funding during 2023/24 and NHS England underspending its central budgets by £1.7 billion to offset these deficits.13

For the 2024/25 financial year, NHS England is forecasting an improved system deficit of £604 million, representing a 0.4% variance against allocation. Under this forecast, 25 systems are expected to meet their financial plans. NHS providers are also forecasting an aggregate deficit of £787 million, which marks a significant improvement from the £1,316 million deficit reported in 2023/24.7

A period of financial stability was observed between 2020/21 and 2021/22, when NHS trusts collectively generated a surplus. This was largely due to the increased funding provided in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which offered greater flexibility in balancing budgets and providing additional services. However, when this additional funding ceased in 2022/23, the financial health across the system began to deteriorate once again.14 The brief period of collective surplus during the pandemic, followed by a return to deficits when additional funding ended, demonstrates a reliance on short-term, reactive funding injections. This “temporary fix” cycle prevents long-term strategic financial planning and investment, as leaders are forced to focus on in-year budget balancing rather than sustained reforms. Without multi-year budgets and a more stable funding model, NHS leaders struggle to make sustained investments and implement reforms, perpetuating a cycle of in-year financial pressures and reactive measures.15

Despite additional funding and concerted efforts to control spending, system-level deficits persist. Analysis by the King’s Fund suggests that NHS trusts received only 90p for every £1 spent on running services for patients in 2023/24.14 This indicates a fundamental gap between the actual cost of delivering services and the allocated funding, pointing to an underlying structural deficit within the NHS. This implies that the NHS is struggling to operate within its current financial means, and existing funding levels are insufficient to sustainably meet rising demand and cost pressures. This situation necessitates difficult choices and a re-evaluation of what the NHS can realistically deliver within its financial envelope.

4.3 Key Cost Drivers: Inflation, Industrial Action, and Demand

Several factors are exerting significant upward pressure on NHS costs. Inflation has had a particularly marked impact since 2023/24. NHS England estimates that non-pay inflation alone cost an additional £1.4 billion in 2023/24, approximately 1% of the total budget, above what was initially budgeted.14

Industrial action throughout 2023/24 also incurred direct costs, such as those arising from cancelled activity. The government provided £1.7 billion in additional funding to mitigate these impacts. NHS England estimates that every additional 0.5% pay increase across NHS staff groups adds approximately £0.7 billion to costs.14 The combined impact of inflation, industrial action pay settlements, and relentlessly rising demand creates a severe financial squeeze. The £22.6 billion additional funding, while appearing substantial, is largely consumed by these existing pressures, leaving little for service expansion or transformative strategic investment. This means the NHS is perpetually playing catch-up, with its budget primarily serving to absorb existing cost increases rather than enabling proactive development. Without a sustained funding increase that outpaces both inflation and demand growth, the NHS will continue to face financial distress, leading to difficult trade-offs and potential compromises on quality or access.

Continually rising levels of demand for NHS services represent a major and persistent cost driver. This demand is fuelled by factors such as population growth and ageing demographics, as well as increasing public expectations regarding healthcare provision.9

Furthermore, a significant shortfall in capital investment is evident. The maintenance backlog for NHS buildings and equipment currently stands at a staggering £13.8 billion. In 2023/24, £900 million of capital funds, originally intended for buildings and equipment, were reallocated to support day-to-day running costs.14 The reallocation of capital funds to cover day-to-day running costs, despite a massive maintenance backlog, represents a disinvestment in the NHS’s long-term infrastructure and capacity. This short-term financial patching undermines future service delivery and efficiency, as dilapidated buildings and outdated equipment hinder modern care delivery and can lead to higher operational costs in the long run. This practice creates a compounding problem: current financial pressures are being alleviated by sacrificing future capacity and efficiency, which will eventually lead to even greater costs and operational challenges for the health service.

4.4 Efficiency Targets and Agency Staff Expenditure

To address financial pressures, the NHS has set ambitious efficiency targets. For 2024/25, systems planned to deliver £9.3 billion in efficiency savings, equivalent to 6.1% of their total allocation. This included a targeted 1.2% reduction in Whole Time Equivalent (WTE) staffing and the overall pay bill compared to 2023/24. As of month 11, systems are forecasting to deliver £8.7 billion in savings, which is only £0.5 billion below the planned target and represents a 21% increase from the £7.2 billion of efficiencies delivered in 2023/24.7

Cash spending on agency staff is forecast at £2.1 billion for 2024/25, which would represent a reduction of £1.4 billion (38%) from 2022/23. This projected spending as a percentage of total pay is the lowest since 2017. Overall workforce levels have increased by 0.1% since the prior financial year, although this is 2.6% higher than the 2024/25 planned levels. Concurrently, the monthly pay bill has fallen by 0.7%, demonstrating the financial benefit of transitioning from temporary to substantive staff.7 The NHS is forecasting delivery of substantial efficiency savings and a significant reduction in agency staff spending. This indicates a concerted effort to manage costs and improve productivity. However, despite these efforts, system-level deficits persist. This suggests that the scale of underlying cost pressures, such as inflation and rising demand, is so immense that even significant efficiency gains are insufficient to achieve financial balance. While efficiency drives are crucial, they are not a panacea for the NHS’s financial challenges. A sustainable financial future will likely require a combination of continued efficiency improvements, a realistic assessment of funding needs that outpace demand and inflation, and potentially a re-scoping of services that the NHS can realistically deliver.

Table 4.1: NHS Financial Performance and Efficiency (2023/24 – 2024/25)

| Metric | 2023/24 | 2024/25 (Forecast) |

| Aggregated System Deficit (£bn) | £1.4 13 | £0.604 7 |

| Provider Deficit (£m) | £1,316 7 | £787 7 |

| Planned Efficiency Savings (£bn) | – | £9.3 7 |

| Forecast Efficiency Savings (£bn) | £7.2 7 | £8.7 7 |

| Forecast Agency Staff Spending (£bn) | – | £2.1 7 |

| % Reduction in Agency Spending (from 2022/23) | – | 38% 7 |

5. Digital Transformation and Procurement Modernization

5.1 Digital Initiatives: AI, Data Analytics, and Digital Therapeutics

Digital transformation is a cornerstone of the government’s ten-year health plan, which includes a strategic agenda to shift from “analogue to digital”.16 Artificial intelligence (AI) is identified as having significant potential for “enhanced health outcomes and system efficiencies.” NHS England’s AI Team is committed to embedding “responsible, ethical and sustainable AI” to improve patient care, optimize resources, and empower staff. Specific applications include AI-driven, clinically safe translation services, which are expected to improve productivity and address health inequalities by ensuring effective communication across all languages.17

There is a renewed focus on scaling proven digital solutions, such as remote monitoring, electronic patient records (EHRs), and digital therapeutics. Digital therapeutics, particularly for chronic conditions, aim to empower patients with tools and knowledge to manage their health, thereby improving overall wellness and reducing pressure on services like GP visits and A&E admissions.18 The emphasis on AI and digital tools is framed around achieving “system efficiencies” and “optimizing resources,” positioning them as key levers to address the productivity challenges highlighted in the workforce plan. However, the critical caveat that AI must be “underpinned by structured data” 18 reveals a fundamental prerequisite. If data quality and integration are poor, the transformative potential of AI cannot be fully realized. This implies that digital transformation is not merely about adopting new technologies but fundamentally about improving data infrastructure and governance. Without high-quality, interoperable data, AI’s ability to drive significant efficiency gains or improve patient care will be limited.

Collaborative approaches are expected to drive advancements in health data integration, with a growing recognition that AI must be “underpinned by structured data.” Vendor-neutral platforms, such as those based on openEHR and FHIR standards, are gaining traction to accelerate interoperability projects. This approach aims to ensure long-term sustainability, flexibility, and to counter vendor lock-in, thereby facilitating seamless data exchange across the health system.18 While digital tools are aimed at improving efficiency and patient access, as seen in the challenges related to GP access, digital solutions can also inadvertently exacerbate digital exclusion for certain populations, particularly those facing language barriers or lacking access to digital technology.3 This suggests that the implementation of digital initiatives must be accompanied by robust strategies to ensure equitable access and prevent the creation of a “digital divide” in healthcare. This requires careful consideration of diverse patient needs and capabilities, ensuring that non-digital access points and culturally competent support remain available.

5.2 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs): Role in Digital Transformation and Data Integration

Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) are positioned as central to breaking down traditional silos within the NHS, particularly for vital services like healthcare interpretation and patient communication. By fostering collaboration, ICSs aim to enhance patient experience and safety.18 The strategic alignment of planning and operations within ICSs is expected to enable leaders to proactively manage staffing pressures, optimize resource allocation, and cultivate supportive environments for staff, thereby ensuring both patient safety and operational efficiency.18

The government’s mandate emphasizes a shift towards a more devolved system, granting greater freedom and flexibility to ICBs and trusts, alongside more choice for patients. ICBs are expected to serve as strategic commissioners, driving the “left shift” towards preventative and community-based care.16 The repeated mention of ICSs in relation to digital transformation, data integration, and strategic shifts, such as the “left shift,” positions them as the primary organizational vehicle for driving change within the NHS. Their role is to bridge the gap between national policy and local delivery, making them the nexus of transformation. The success of NHS reforms, including digital adoption and financial sustainability, therefore heavily relies on the effectiveness and maturity of ICSs. Challenges in their financial position or operational capacity could significantly impede these crucial transformations.

A core objective of the evolving operating model is to shift towards “a more preventative and empowering model of care, particularly in relation to higher intensity users, which is delivered closer to people’s homes”.16 This fundamental strategic change requires that “a smaller proportion of NHS spending must go into acute hospital-based activity,” with a corresponding boost in capacity within primary, community, and mental health settings, alongside workforce re-engineering. This “left shift” implies a radical reallocation of resources and a transformation of care pathways. It will likely face significant political and operational resistance, especially if it involves perceived reductions in acute services. Its success hinges on the ability to demonstrate tangible improvements in community-based care before acute capacity is reduced, and on overcoming the inertia of historical funding allocations.

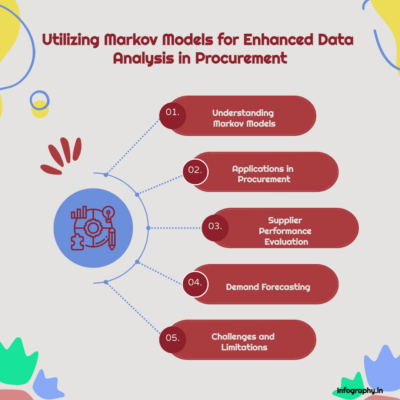

5.3 Procurement Landscape: Act 2023, Social Value, and Supply Chain Efficiency

The procurement landscape for the NHS is undergoing significant modernization. The Procurement Act 2023, effective from February 2025, aims to improve public sector procurement by shifting from the “Most Economically Advantageous Tender” (MEAT) to the “Most Advantageous Tender” (MAT) approach. This change prioritizes long-term societal benefits over mere cost, emphasizing transparency, inclusivity, and a community focus in procurement practices.19

The updated Social Value Model (PPN 002) becomes mandatory for central government departments from October 2025, requiring a minimum 10% weighting for social value in tender evaluations. This model supports five government missions, including “Build an NHS fit for the future,” with eight specific outcomes, such as sustainable procurement practices, local job creation, and promoting well-being. While not strictly mandated, NHS bodies are strongly encouraged to adopt these principles.19 The shift from MEAT to MAT and the mandatory 10% social value weighting (for central government, encouraged for NHS) represents a significant policy move away from purely cost-driven procurement. This means NHS procurement decisions are increasingly expected to consider broader economic, social, and environmental benefits, not just the cheapest price. This change could lead to more sustainable and ethical supply chains, support local economies, and improve community well-being. However, it also adds complexity to procurement processes and requires NHS bodies to develop new capabilities in measuring and embedding social value, potentially impacting short-term cost efficiencies.

NHS Supply Chain estimates that the NHS collectively spends approximately £8 billion annually on buying medical equipment and consumables.21 Its key objectives included delivering £2.4 billion in savings and achieving an 80% market share by 2023-24. While NHS Supply Chain claims to have exceeded its savings target, the National Audit Office (NAO) report notes that it is “not yet fulfilling that potential” and faces challenges with voluntary adoption by trusts.21 Although 99.5% of trusts purchase some goods through NHS Supply Chain, significant purchasing still occurs outside the centralized system.22 Despite NHS Supply Chain’s potential for aggregated purchasing power and savings, its voluntary adoption by trusts limits its overall effectiveness. Trusts continue to make significant purchases outside the centralized system, hindering the realization of full economies of scale. This suggests a lack of strong incentives or perceived value for trusts to fully comply. The gap between national procurement strategy and local purchasing behavior creates inefficiencies and means the NHS is not maximizing its collective buying power. Greater alignment and potentially stronger incentives or clearer mandates are needed to optimize procurement savings and ensure the system benefits from its scale.

6. Patient Experience and Public Perception

6.1 Hospital Inpatient Experience: Satisfaction, Waiting Times, and Staffing

Patient experience in NHS hospitals reveals a complex picture of sustained positive interpersonal interactions amidst declining overall satisfaction and growing frustration with systemic issues. The Care Quality Commission’s (CQC) 2022 annual survey of hospital inpatients indicated that overall patient satisfaction levels have remained largely static since 2021, but a longer-term decline is evident in most areas compared to previous years. The proportion of people who rated their overall inpatient experience as nine or higher out of ten declined to 50% in 2022, down from 56% in 2020.23

Despite these trends, the majority of respondents (81%) consistently reported having confidence and trust in the doctors treating them, a figure unchanged from 2021. Similarly, over four-fifths (82%) felt they were “always” treated with dignity and respect, also unchanged since 2021. Responses regarding staff support for fundamental needs generally remained stable in 2022, following a significant decline in 2021. For instance, 70% reported “always” getting help to wash or keep themselves clean (unchanged from 2021, but down from 75% in 2020), and 75% were “always” offered food that met their dietary needs (up from 74% in 2021). Most respondents (77%) felt they received “the right amount” of information about their condition or treatment, unchanged from 2021 but lower than 80% in 2020.23 Patients largely report being treated with dignity and respect by staff, and trust in doctors remains high. However, overall satisfaction is declining, and there is growing frustration with waiting times and perceptions of insufficient staffing. This suggests a disconnect: while individual interactions with staff are positive, the systemic failures, such as long waits and perceived understaffing, are eroding overall patient experience and confidence in the system. The dedication of frontline staff is mitigating some of the negative impacts of system pressures, but it cannot fully compensate for systemic capacity and access issues. Addressing these operational challenges is crucial to prevent further erosion of public satisfaction and trust.

A major source of frustration is waiting times. The survey highlights growing dissatisfaction, with four in ten (41%) people scheduled for planned treatment reporting that their health deteriorated while waiting to be admitted in 2022. Of these, 24% stated their health got “a bit worse” and 17% “much worse.” Over a third of respondents (39%) who were in hospital for elective care wished they had been admitted sooner. A significantly higher proportion of people reported waiting longer for a bed on a ward after arriving at the hospital in 2022 compared to previous years (18% felt they “had to wait far too long” in 2022, up from 8% in 2020).23 The finding that 41% of patients waiting for planned treatment experienced health deterioration is a severe consequence of the elective backlog. This moves beyond mere inconvenience to direct harm, potentially requiring more complex and costly interventions later. Long waiting lists are therefore not just administrative challenges; they have a tangible, negative impact on patient health and well-being, underscoring the urgency of addressing the elective care backlog.

Perceptions of staffing levels have also deteriorated. Just over half of survey respondents (52%) felt there were “always” enough nurses on duty to care for them in the hospital in 2022, a decrease from 62% in 2020. Similarly, almost two in three (62%) reported they could “always” get a member of staff to help when needed, down from 67% in 2020.23

6.2 Primary Care Access: Challenges and Consequences

Primary care access presents significant challenges, as detailed in Section 2.6. These include increased demand, a declining number of GPs per patient, long waiting times for appointments (5 million people waiting over two weeks in March 2024), notable regional variations in access, and persistent difficulties in contacting practices.3

Digital exclusion exacerbates these issues, particularly for non-English speakers, who struggle with online systems and language barriers. They find it difficult to use apps or systems for appointments, read emails/texts due to limited English proficiency, and often distrust translation software.3

The difficulties in accessing timely primary care services create a “domino effect,” pushing patients into more acute and expensive parts of the system. When patients cannot secure timely GP appointments, especially for urgent needs, they frequently resort to other services like NHS 111 (47% of those with difficulty accessing GP care) or A&E (24%).3 This not only increases pressure on emergency services but also means conditions may worsen before treatment, leading to potentially avoidable hospital admissions. Investing in and strengthening primary and community care is therefore a preventative measure that can significantly reduce downstream pressures on hospitals and emergency services, leading to better patient outcomes and more efficient resource use across the entire health system.

There is an increasing reliance on emergency departments for dental issues, with “DIY dentistry” becoming common due to long NHS dental waiting lists. Community pharmacy closures, which disproportionately affect deprived areas, further compound access challenges across the wider healthcare system.3 The disproportionate impact of pharmacy closures on deprived areas and the prevalence of “DIY dentistry” highlight significant equity concerns within the strained system. Vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women and children, also face higher barriers to dental care. This suggests that the strain on the system is not evenly distributed, with those in greatest need often facing the steepest challenges in accessing care. Policy interventions must explicitly address health inequalities and ensure that efforts to improve access and efficiency do not inadvertently disadvantage already vulnerable populations.

7. Future Direction and Policy Implications

7.1 National Priorities for 2025/26: Key Performance Targets

NHS England has outlined specific national priorities and success measures for 2025/26, framing it as a “reset moment” for the health service.2

For elective care, targets include improving the percentage of patients waiting no longer than 18 weeks for treatment to 65% nationally by March 2026, with every trust aiming for a minimum 5% point improvement. Similarly, the target for patients waiting no longer than 18 weeks for a first appointment is set at 72% nationally by March 2026. A key objective is to reduce the proportion of people waiting over 52 weeks for treatment to less than 1% of the total waiting list by March 2026.2

In cancer care, the aim is to improve performance against the 62-day treatment standard to 75% by March 2026, and the 28-day Faster Diagnosis Standard to 80% by the same date.2

For emergency care, targets include improving A&E 4-hour waits to a minimum of 78% of patients admitted, discharged, or transferred within that timeframe by March 2026. There is also an objective to achieve a higher proportion of patients admitted, discharged, or transferred from A&E within 12 hours across 2025/26 compared to 2024/25. Ambulance response times for Category 2 calls are targeted to improve to an average of 30 minutes across 2025/26.2

In primary care, priorities include improving patient experience of access to general practice, as measured by the ONS Health Insights Survey, and increasing the number of urgent dental appointments by 700,000.2

From a financial performance perspective, the NHS aims to deliver a balanced net system financial position for 2025/26 and reduce agency expenditure by a minimum of 30% on current spending across all systems.2

These 2025/26 targets are highly ambitious, particularly for elective care and emergency services, given the current performance levels and the persistent financial and workforce pressures. Achieving these will necessitate not just incremental improvements but potentially transformative changes in service delivery and efficiency across the system. The significant gap between current performance and these targets underscores the immense challenge facing the NHS. Success will depend on the effective implementation of the workforce plan, robust digital transformation, and sound financial management, alongside a realistic assessment of what is achievable within the given funding envelope.

7.2 Evolving Operating Model: Structural Changes and Devolution

The government’s ten-year health plan outlines significant structural reorganization for the NHS. This includes the planned abolition of NHS England, with its functions to be integrated into the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). This integration is accompanied by a substantial 50% reduction in the combined workforce of NHS England and DHSC. Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) are also slated to face 50% cuts to their running and program costs.16

The new operating model, to be detailed in the ten-year health plan and formalized through primary legislation, is envisioned as “rules-based, provides earned autonomy and incentivises good financial and operational performance.” It aims for a shift from a “top-down centralised control” model to a more devolved system, granting greater freedom and flexibility for ICBs and trusts.16 The plan proposes both the abolition and integration of NHS England into DHSC, which implies greater central control, and a simultaneous shift towards greater devolution and autonomy for ICBs. This apparent contradiction raises questions about how these two forces will be balanced in practice. Centralized cuts to NHS England’s workforce might reduce its capacity to effectively support local devolution. The success of this new operating model hinges on a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, and a genuine empowerment of local systems, rather than simply centralizing control under a new guise. Past failures suggest that structural reorganizations undertaken amidst financial and operational pressures are highly disruptive and challenging to implement effectively.

A core objective of this evolving model is the “left shift” strategy: moving towards “a more preventative and empowering model of care, particularly in relation to higher intensity users, which is delivered closer to people’s homes”.16 This necessitates that “a smaller proportion of NHS spending must go into acute hospital-based activity,” with a corresponding boost in capacity within primary, community, and mental health settings, alongside workforce re-engineering. ICBs are central to driving this transformation.16 This “left shift” strategy explicitly calls for a radical reallocation of resources and a fundamental transformation of care pathways. It will likely face significant political and operational resistance, especially if it involves perceived reductions in acute services. Its success will depend on the ability to demonstrate tangible improvements in community-based care before acute capacity is reduced, and on overcoming the inertia of historical funding allocations and established service models.

Learning from past reforms is crucial, as historical challenges in translating new operating models into practice, especially amidst operational and financial pressures, are well-documented. Previous reorganizations and staff cuts, such as the 36% reduction in NHS England staff between July 2022 and May 2024, have impacted implementation effectiveness.16

7.3 Interdependencies and Cross-System Challenges: Social Care Impact

The critical link between social care capacity and NHS flow is consistently highlighted by the significant number of patients delayed for discharge from hospitals. While only a minority of these delays are solely attributable to social care, the broader “capacity” issues often involve jointly commissioned services or a lack of suitable social care options post-discharge.4

The adult social care sector in England faces a severe workforce crisis rooted in low wages, chronic underfunding, and a lack of a strategic workforce plan. Care workers earn significantly less than their NHS counterparts, with an average pay gap of 35.6%.8 This disparity contributes to high turnover rates (24.8% in 2023/24) and a reliance on costly agency staff. While international recruitment has temporarily alleviated some shortages, recent policy changes, such as increased visa fees and minimum salary thresholds, are impacting this pipeline, leading to a sharp decline in applications.8 Financial deficits are prevalent among social care providers, with 29% operating at a deficit and 3 in 10 having closed parts of their organizations due to cost pressures.8 These workforce challenges and underfunding in social care directly impact the NHS’s ability to discharge patients, creating a bottleneck that exacerbates hospital bed occupancy and A&E pressures.4